Tim Flannery is a fear-mongering, doom-laden “Alarmist of the Year” in his environmental commentary and interpretation of climate-change science.

That’s what his critics would have you believe. Take this statement, for example: “On the balance of probabilities, the failure of our generation on climate-change mitigation would lead to consequences that would haunt humanity until the end of time.”

The trouble is, that’s not a Flannery quote, it’s a quote from Professor Ross Garnaut, one of the most eminent economic reformers of modern Australia, in his final report, released in September this year: the Garnaut Climate Change Review.

You don’t need to read Flannery to become alarmed at climate change, you just need to read the science.

What puts Tim Flannery at the cutting edge of the climate-change debate is his predisposition to conceptualise and visualise unknown worlds, core to his palaeontology background. He might have rocks in his head, but he is far from crazy. He knows the past and looks to the future.

This is what sets Tim Flannery apart – his ability to see through time and to communicate this future. He is able to see across generations. He can visualise our world in fifty years, and this vision haunts him.

With every hit he receives, he probably wants to put his head in the sand like a good palaeontologist and leave us to it. Instead, he feels his responsibility acutely and the storyteller in him sends him out again and again to spread the word.

The truth is that a future of unmitigated climate change really will haunt humanity until the end of time. The world’s climate scientists tell us that we need to keep greenhouse gas concentrations in our atmosphere below 450ppm CO2 (carbon-dioxide equivalent) if we are to have even a 50 per cent chance of keeping global warming below a critical threshold of 2 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

Professor Garnaut says that Australia’s share of a 450ppm agreement would involve reducing emissions in the order of 25 per cent by 2020 and 90 per cent by 2050.

The implications of a global stabilisation target of 450ppm for Australia and the world are simple, but profound. No matter which phase in the industrial revolution countries are in, we are going to have to completely decarbonise the world’s energy-production systems and we are going to have to restore a positive carbon balance in the world’s natural landscapes – our forests and our agricultural lands – and we have forty years to do it. You can understand Tim’s urgency.

We need to reframe the industrial revolution. We need to build a 21st-century economic system that is profoundly different to that of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Yet while the political and technical challenges are enormous, we are finally coming to realise just how economically feasible this is. In the early years, business can make a profit and households can save money when they invest in technologies such as building insulation, fuel efficiency and solar water heating. With the exception of currently unproven carbon capture and storage technologies, we actually have all the technologies in place today to fix the problem. Professor Garnaut is unequivocal: “the cost of action is less than the costs of inaction.”

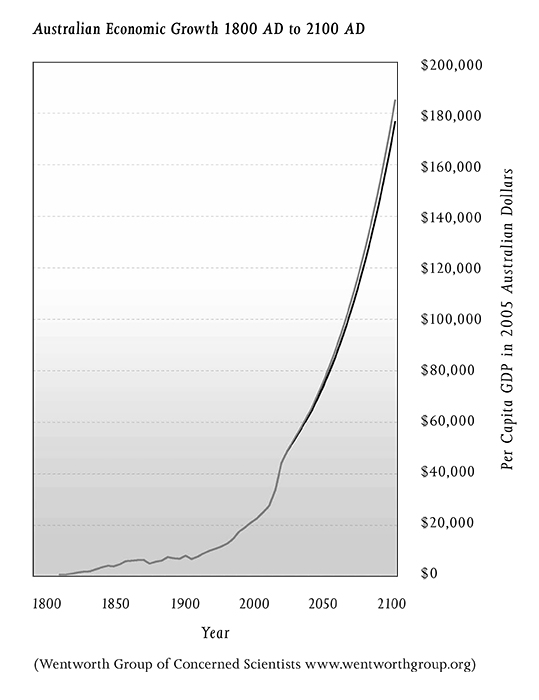

The graph below highlights the implications of achieving a 450ppm CO2 target for the Australian economy. It is based on Australian Treasury projections of future economic growth in Australia.

The grey line shows the explosion in wealth expected between now and the end of this century if GDP continues to grow in the order of 1.5 per cent per capita per annum.

The black line shows you what a reduction in GDP really means if we commit to stabilising greenhouse gas concentrations at 450 ppm CO2 by 2050.

No sane human being would risk runaway climate change on the basis of this information.

This graph should be on T-shirts because it conveys a most hopeful message: a price on carbon will drive the next industrial revolution.

While the mitigation of energy generation is a must-do if we are to have any chance of achieving such a target, this focus has masked the many opportunities for Australia to harness the power of restoring terrestrial carbon (bio-sequestration).

The solution to climate change has not one, but three components:

—Energy technology (to produce carbon-pollution-free energy) – this needs to provide 50 per cent of the solution;

—Energy efficiency (using less energy and in the process saving money) – 25 per cent;

—Landscape management (we need to let nature help us, because trees and soils absorb carbon) – 25 per cent.

Landscapes absorb vast quantities of carbon, so by reducing land clearing and increasing carbon stocks through revegetation and soil carbon, landscape management can become a fundamental part of controlling the CO2 balance in the atmosphere.

Restoring terrestrial carbon by managing our landscapes is a very different approach from emissions reductions because it actually makes a positive contribution to stabilising the world’s climate system by drawing carbon pollution out of the air. This is an unbelievably important concept. Healthy landscapes can become more valuable than cleared ones because rainforests and restored river basins store vast quantities of carbon.

The scale of this opportunity globally is almost unimaginably large. Even a small gain is of enormous significance. Just one of a dozen bio-sequestration opportunities currently available has the potential to reduce Australia’s annual emissions by over 50 per cent each year for the next fifty years. Ross Garnaut agrees. He believes that that full utilisation of bio-sequestration could “favourably transform the economic prospects of large parts of remote rural Australia.”

Investments for storing carbon in terrestrial landscapes can be targeted to produce multiple environmental and economic benefits. For example, restoring native vegetation along the nation’s rivers, wetlands and estuaries would improve water quality and re-connect native vegetation across our vast, fragmented landscapes. In addition, it would increase soil carbon in agricultural landscapes, which improves the productivity of our soils, which have been in slow decline over the past two centuries.

There is one other great economic and institutional reform that we must embrace, one which on face value seems a little mundane compared to the other two of decarbonising the world’s energy-production systems and putting an economic value on landscapes that draw and store carbon from the atmosphere, but it is one that lies at the very heart of our current environmental problems.

We are now aware that our future prosperity is linked to effective stewardship of nature: our land and water, a stable climate, clean air, healthy coasts and marine resources. We now know that without stable, functioning natural systems, our economic prosperity is transient and intergenerational financial security is a mirage. We are in the early stages of the twenty-first century, yet our environmental accounting practices are in the Dark Ages. If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.

It is one of the great failures of public policy of our generation and it is at the core of our environmental problems. It has resulted in policy and land-use decisions that have caused significant and unnecessary damage to our natural environment, and it has resulted in the massive waste of billions of dollars of public funds aimed at repairing this damage.

Australia needs to confront the challenge of managing our natural capital with the same discipline with which we manage our economy. Australia needs an environmental accounting system, including carbon accounts, that will inform government, business and community decision-making.

Building the National Environmental Accounts of Australia will change the way we manage Australia: the design of our cities, how and where we produce our food and fibre, and how we direct public and private investments as we strive to improve and maintain the health of our environmental assets.

Today we wouldn’t dream of managing the economy without rigorous accounting standards for our personal accounts, for business dealings and for managing the national economy. Environmental accounts are fundamental to dealing successfully with the 21st-century challenges of stabilising the world’s climate systems and managing nature.

With three great reforms – decarbonising the world’s energy production systems; putting an economic value on landscapes that draw and store carbon from the atmosphere; and building environmental accounts – our generation has the opportunity to transform the economics of the 21st-century, and in doing so, transform the management of nature and, with it, our place in history.

But as Tim Flannery so brutally puts it, there is no time to lose.

Peter Cosier is director of the Wentworth Group of Concerned Scientists, who came together in 2002 to pursue reform in the management of Australia’s land and water resources. He was deputy director-general of the NSW Department of Infrastructure, Planning and Natural Resources and, for six years, a policy adviser to former environment minister Robert Hill.

CONTINUE READING

This correspondence discusses Quarterly Essay 31, Now or Never. To read the full essay, subscribe or buy the book.

This correspondence featured in Quarterly Essay 32, American Revolution.

ALSO FROM QUARTERLY ESSAY