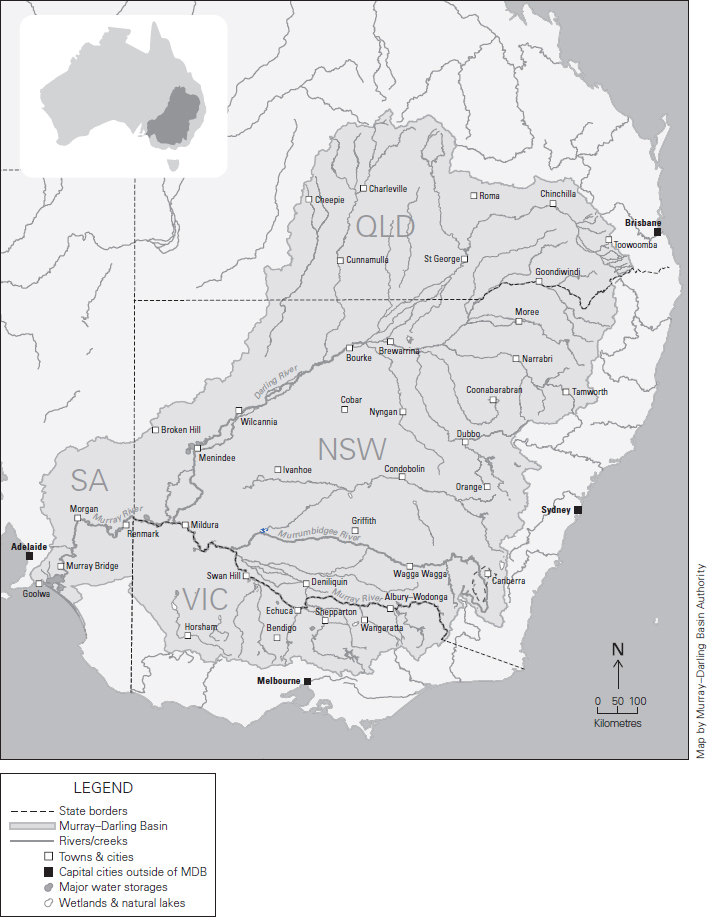

I’ve come to think of the Murray–Darling Basin as being like a tree, except the sap runs not from root to twigs but in the other direction. The roots and trunk are in South Australia. Here the river runs pea-green between red cliffs through semi-desert country to the vast sheets of water that form the lower lakes, the Coorong and the sea. The main branches of the tree are the Murray itself, forming most of the border between New South Wales and Victoria, fed by the mighty Murrumbidgee and its tributaries and the rivers of Victoria. The other main branch is the Darling, or the Barwon–Darling, to give it both its northern and southern names. Its tributaries loop to the Great Dividing Range west of Sydney and splay into the braided floodplains of the tropics. The smaller branches and twigs spread across the inland, each one with a story, or many stories. Clancy of the Overflow, who worked on the Lachlan River before he went “to Queensland droving … down the Cooper River, where the western drovers go.” The Drover’s Wife, who lived by a dried-up creek in the Henry Lawson story. It was probably a tributary of the Darling, although recent reimaginings relocate her to the Snowy Mountains. The European names of the rivers are gestures to the history of white nation-building – Lachlan, Macquarie, Darling, the Murray itself.

There are older stories. The Rainbow Serpent, which in the stories of the Barkandji lives in the waterholes of the Lower Darling, or the Barka as they prefer to call it. Or Ngurunderi, whose pursuit of Ponde – a Murray cod – created the channel of the Lower Murray.

You can give the figures – 77,000 kilometres of rivers, 2.6 million people, forty Aboriginal nations, 120 species of waterbirds – but they are abstractions from the reality.

It seems wrong that the word “basin” is so utilitarian, conjuring up images of kitchen implements and dishwater. This is a mighty thing. It covers more than a million square kilometres. One of the things that makes it hard to understand, to conceptualise, is its size. The water engineers call it one of the largest drainage areas in the world, which again makes one think of sinks and plugholes.

But it can also be thought of as a vast, cupped hand. This is how Badger Bates, a Barkandji elder, describes it. He was raised on the Barka and taught the traditional ways by his grandmother and extended family. He grew up to be a stockman and a park ranger. He says he never learnt to read and write properly, but today, at seventy-three, he carries himself with a natural authority that the bureaucrats and politicians struggling to govern the Basin can only envy. He stretches out his arm. “Here is my left hand, and in my palm the Barka starts. And here my fingers running to my palm are the Warrego, the Barwon, the Culgoa. Then here, my thumb joint, that is Wentworth, where the Barka meets the Murray. Then across where my left arm meets my shoulder, my body beyond” – he gestures to his chest, his skinny, hardened torso – “that is South Australia, right down to them lakes. And my right arm, here runs the Murray. So, our duty as Barkandji people is to fight for this river, to give them all water. We are connected.”

But at the moment, and too many times in the last decade, the Darling doesn’t run.

Water connects people, but it also divides. If politics is how human societies decide on the sharing of resources, wealth and power, then in a dry country water is indubitably, essentially and unavoidably political. The Basin and its water politics are in the news because of allegations of corruption and water theft, because of dead fish and angry irrigators, and because a royal commission in South Australia has suggested one of our important government organisations, the Murray–Darling Basin Authority, is dishonest, incompetent and acting outside the law. The narrative concerns the Murray–Darling Basin Plan and its implementation. To the management of the Murray–Darling we can attribute the rise of the Shooters, Fishers and Farmers Party, and an increasing atmosphere of panic – mixed with vaunting ambition – in the National Party, extending into the Coalition. And, most likely, Labor will not be able to win government unless it can address water politics, and with it one of the political fractures of our time: the divide and mutual incomprehension between those who earn their living directly from land and resources and those who don’t.

There is a conventional, city-based view of rural Australia as locked in a time warp, unchanging and resistant to change. It is a dangerous and sentimental misunderstanding – as simplistic and out of touch as its rural-based counter, the view of city folk as soft-handed, soft-headed and divorced from hard realities. The speed of change for those who learn their living from the land outstrips anything city dwellers have dealt with in recent decades. Technology and mechanisation has devastated rural employment. New cropping methods – laser ploughing, preserving stubble on the soil – have had to be learnt, and in turn have kept more water in the soil. Free-market reforms have seen the death of the Australian Wheat Board and the other bodies that governed the production and marketing of agricultural products. Agricultural policy has been at once centralised and fragmented. Farmers have become futures traders, brokers in their own production. Agriculture and food production have been rapidly corporatised, from paddock to supermarket and container ship. In the 2015–16 Agricultural Census, there were about 86,000 farms in Australia. Ten years ago, there were 135,000.

This speed of change, and the stress and dislocation it causes, is the backdrop to water politics. Throughout the modern history of Australia, the Murray–Darling Basin has challenged our ability to operate as a nation. Now, it may bring politics as normal undone.

Since 2012, the Murray–Darling Basin Plan has sought to claw back the allocation of water to farmers in the area usually described as the food bowl of our nation (although, thanks to the increasing dominance of cotton, these days people prefer to talk of food and fibre). The Basin is Australia’s most important agricultural region, producing around one-third of the national food supply, and a total of $24 billion in agricultural products. Australia is unusual in the world in that it can more than feed itself – producing more agricultural products than we can consume. That is thanks to the Basin. More than 3 million people rely on the river system for their drinking water. If you eat nuts or fruit or bread or meat or rice or vegetables, drink milk or wear cotton, then you are likely tangibly connected to the Murray–Darling.

But we are all in trouble. Over the latter part of the last century, it became clear that the river system was at breaking point. It could die. All that went with it – money, livelihoods, sense of nation – was at risk. There were many indicators, including salinity, blue-green algae, fish deaths and the closing of the Mouth. There were billabongs that smelt of rotten eggs. The Murray–Darling Basin Plan, devised over many years, is an attempt to solve that problem. It is the first attempt to manage the Basin as a whole, and to make its use sustainable. That means striking a different balance between water use and the environment, taking water back from farmers and using it to better manage the health of the river.

We are now at the halfway point of the Plan’s twelve-year implementation and things seem to be falling apart. Meanwhile, people in the cities – and even those who live in the Basin – struggle to understand what the river system is and how it works. The water flows, usually, but the information doesn’t. The water engineers of the Basin talk in terms of valleys – each river and each catchment. But the Basin is shallow, and these are not valleys in the European sense, each community divided from the other by hills and mountains. Rather, the people of the Basin are a society without being a community. A society in the sense that they live in an ordered, rule-bound way, the relationships between them governed. Not a community, because they struggle to recognise common interest.

In the Murray–Darling Basin, the authorities joke, everyone downstream is a wastrel, and everyone upstream is a thief. Only I, the person drawing water in this spot, for these crops, in this way, truly understands the value of the water and how to use it.

The Basin is a plumbed landscape – one of the most plumbed in the world. In the Southern Basin, it is tightly controlled. The Murrumbidgee and the Murray are reliable rivers, fed by snow melt in spring as well as by tributaries, and defined by big dams and storages – the Hume, the Dartmouth and others. Water is ordered up and delivered by rivers, pipes and channels to its end use. The Northern Basin is different. Here the rivers are boom and bust.

For water users, there is a welter of rules, different from state to state and valley to valley, governing exactly how the water is managed and shared. For all but the experts – and even for some of them – the rules are impenetrable. Taking a very broad brush to great complexity, one can own a licence to take water, and then an allocation is made against that licence, which varies depending on the season and the type of licence held. There are general security licences – the majority in the Basin – and high security licences, more likely to be held by the owners of crops, such as grapevines and fruit and nut trees, that remain in place for many harvests, needing water each year. There are also rules about “supplementary flows” – when the river is in flood or running high. Both licences to take water and allocations can be traded. Add to this that water users can in most places carry forward what they don’t use, sometimes for as long as ten years, and that in some areas water is increasingly being stored in private dams, and it becomes hard to know why, for example, the farmer downstream or upstream or across the river is able to grow a crop when you are dry.

The Bureau of Meteorology gathers the information on water trading from the states, but publishes only at a macro level. Finding out how the system works in any particular area is almost impossible for an outsider. Attempts to penetrate the complexities of Basin management are not helped by the desiccated language of the bureaucracy, and of the water engineers who have, since before federation, dominated irrigation – the white man’s dream of creating gardens in the desert. They speak of “events.” That usually means that it has rained. A “major event” means that it has rained a lot. Sometimes an “event” means a release of water from a dam or storage. Then there are the key terms that underlie the Basin Plan, such as the sustainable diversion limit – a cap, in theory, on how much water can be extracted, which is then translated into caps for each area. This is not only dead language, but also confusing, even a lie, because the sustainable diversion limit is not sustainable, and may not be a limit. Academic critics of the Basin Plan have described water politics as having entered a “post-truth world.”

Furthermore, the numbers are hard to grasp. The language of water management is megalitres and gigalitres – units most people can’t visualise. A megalitre is 4 million cups of water, or a million one-litre milk bottles, or about 5000 baths. A gigalitre – the units in which the macro policy of the Basin is determined – is a billion litres, or a thousand megalitres. Sydney Harbour contains about 500 gigalitres. The average annual rainfall in the Murray–Darling Basin supplies about 508,000 gigalitres of fresh water, of which 94 per cent evaporates or transpires. In some seasons, more evaporates than falls as rain. About 2 per cent of the rain recharges groundwater aquifers. The remaining 4 per cent, or about 24,000 gigalitres, runs into streams and rivers. Another 1200 gigalitres or so is transferred from elsewhere, such as from the reliable waters of the Snowy River, diverted beneath the Great Dividing Range to the Murray and Murrumbidgee, making possible the rich green irrigation areas of Griffith and Leeton. Huge amounts are “lost,” as the engineers say, to wetlands, evaporating or seeping into the soil – not really a loss, but a natural part of the river. Total water use by humans in the Basin, some from groundwater but mostly from the rivers, is 12,903 gigalitres a year, or about twenty-six Sydney Harbours. Most of that is for agriculture. About 5000 gigalitres flows to the sea.

But these are averages, and the large figures tell us little or nothing about any particular year, or any particular place. The Murray–Darling Basin Plan is macro policy, governed from Canberra. But it plays out in landscape that farmers and locals know with the intimacy of a lover.

Jody Swirepik is the Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder – the woman in charge of managing the water that has been clawed back for the environment under the Basin Plan. She describes a recent visit to the Lachlan River, where there was controversy over the release of 22 gigalitres of environmental water to flow down the length of the river, past drought-stricken properties to the Cumbung Swamp, the wetland at the junction of the Lachlan and the Murrumbidgee. The NSW Minister for Water, Melinda Pavey, said that the Water Holder was “pouring water down the river without any regard for our communities doing it tough.” (In fact, the releases of water had been planned with the NSW government.)

I had been on the Lachlan a fortnight before Swirepik’s visit. Irrigators told me they didn’t understand what the Water Holder was trying to achieve. They worried an attempt was being made to maintain the swamp in a condition that could not be sustained, and that if the swamp “fell over” later, irrigators would cop the blame. Speaking in her office in Canberra, Swirepik reflected on how macro policy meets the realities of landscape: “The river is not a canal. It has all these complexities.” For example, she had been told about a bank that used to be in the swamp – about a foot high for most of its length, which had held water back, creating a wetland and reedbeds. The locals told her that sometime in the last decade that little bank had been removed – nobody knew by whom. As a result, the wetland plants had disappeared. Did the Water Holder know about the removal of that little bank before her visit? Swirepik is sure some of her staff would have known. “But you have to get out into the landscape. There are so many stories of the river, you know, pub stories from twenty years ago, or people’s recollection that there used to be a wetland here, and that they saw tens of thousands of birds breeding there and haven’t seen that recently.”

These stories of the river are increasingly contested, as the engineers attempt to model and restore some portion of “natural” flows. The irrigators on the Lachlan, in their interviews with me, posed the question of what the Water Holder thought the “natural” state of the Cumbung Swamp would have been, and what “sustainable” might look like. What is natural? What people remember from their childhood, what the traditional owners have recorded in stories, or what the water engineers’ models tell us would once have happened before we built dams and locks and weirs and drew away so much of the water for our own use? And how to account for climate change? Swirepik comments: “The landscape has been changed over decades and sometimes we don’t exactly know how … We are not trying to change things back to natural. That’s not possible … We need to identify what areas of habitat and environmental values can be supported or restored.” She agreed with the Lachlan River landholders that the Water Holder needed to work at the property level, to come to joint understandings of what can be sustained.

The natural state lies outside living memory, in the realm of dreaming and anecdote. In both the real and the political landscape of the Murray–Darling Basin, nature is often referred to, used as a justification for action, but increasingly it is out of reach, a concept rather than a reality.

Some of the stories of the river are well known and can be read on signposts at tourist spots. Some of them are buried or disputed. Parts of the landscape speak loud. Some speak soft, and some have lost their stories entirely.

*

The Murray–Darling Basin Plan is at once a water management plan, an ecologically driven document and a political compact, all embedded in narratives of land and water. One of my aims in this essay is to rescue those narratives from the abstract, explain the Plan and the system it is trying to govern, and explore why things seem to be falling apart. At the heart of the narrative is the collision between the realities of the landscape – the intimate details, the banks and tributaries, the complexities of community and society – and macro policy, the affairs of the nation.

I did a lot of driving – all over the Basin. Rural Australia no longer lies at the heart of our national narrative, but as I travelled snatches of poetry came to me. The sunlit plain extended. The drover’s life has pleasures city folk never know. A land of drought and flooding rains. Its beauty and its terror. In the lower lakes, sun played on sheets of water, and I could smell the sea and hear the roar of breakers on the beach beyond the dunes. On moonlit nights I fancied I could understand why so many stories of the Ngarrindjeri tell of people travelling from the lake country to the sky.

Around Loxton in the South Australian Riverland, and over the border near Mildura, I saw hectares and hectares of new plantings – mostly almond trees, catering to the trend for almond milk, driven in part by concern about the impact of dairy cattle on a warming planet. Alongside the almond trees were abandoned grapevines, bulldozed into piles or left to stand like skeletons, fingers pointing to the sky, and in between red dust – a reminder that, without water, this is desert.

I drove across the Hay Plains, so flat I could detect the curvature of the earth. The road trains swam towards me through water mirages. There were curtains of rain when I was there, and the overpowering smell of water on dry. The land glowed orange. So did the low walls of newly constructed private dams, springing up on land never previously irrigated.

On the road from Wilcannia to Broken Hill there were willy-willies all over the plain, the columns of red dust rising to the sky like pillars in the vast hall of the inland.

Drought is an abstract word when spoken in the city – defined by figures of rainfall, or “events.” But around Dubbo and Narromine, it became real. The sky was dirty-brown because of the dust. The paddocks looked as though they had been targeted by a vast vacuum cleaner. I stopped in the tiny, evocatively named town of Nevertire, on the edge of the saltbush country that extends west to the deserts of the interior, and my car was buffeted by the big road trains carrying fodder to cattle inland. Not far away was the Auscott cotton gin factory. No cotton was being grown there, because there was no water, but the ash-coloured waste from the last crop was bundled in the paddocks, and fur balls of white were strewn by the side of the road – baubles on khaki.

Further north, pursuing the Darling to its headwaters, I drove the road between Dirranbandi and St George. In drought, wildlife comes to the roads, because tiny run-offs of condensation or rain allow vegetation to survive on the verge. That means roadkill. For some reason this road was particularly bad. It was like driving through an abattoir or a deli counter. Raw meat, dried meat, fermented meat and the constant crunch of bone.

Further east, as I approached the rim of the Basin and the Darling Ranges, even the prickly pear – that introduced scourge of the inland, which once made 40,000 square kilometres of farming land unproductive – was wilting. The spiky pads were wrinkled and pointing to the ground.

It was a big journey and my companions included pride, fear, horror and awe. Sentimental, perhaps, but often I had a lump in my throat and tears in my eyes. The beauty and the terror. The vastness of the Basin, and the wonder and the awfulness of our attempts to manage it.

CONTINUE READING

This is an extract from Margaret Simons's Quarterly Essay, Cry Me a River: The Tragedy of the Murray–Darling Basin. To read the full essay, subscribe or buy the book.

ALSO FROM QUARTERLY ESSAY