THE GREAT DIVIDE

Response to Correspondence

Tackling Australia’s housing mess in a Quarterly Essay was a daunting task, partly because it’s a big, complicated mess, but also because everyone has a firm opinion on the subject and a lot of smart people have spent their lives studying it, and I’m not one of them. But the responses to the essay have been plentiful, informative and gratifying, including the ones from those who weren’t impressed with what I had written; as always, you learn more from those who disagree with you than those who agree. I’m grateful for all of them.

Brendan Coates and Joey Maloney at the Grattan Institute didn’t like my suggestion of fast trains to open up regional areas for viable commuting to the city, which they called an “unfortunate misfire” and Peter Tulip thought I overemphasised the impact of tax concessions. I want to deal in detail with each of these two responses because I learnt from them, and they get to the heart of the problem – and the solutions.

Brendan and Joey think I too easily dismissed the potential for densifying the suburbs – that is, building more medium-density housing in good locations that use existing infrastructure. They tell us that, going into the pandemic, Australia had 400 homes per 1000 people, among the least amount of housing stock per person in the developed world, and we have some of the least dense cities. The reason is simple, they say: the processes that dictate what gets built where are hugely biased against change.

The answer, they assert, is equally simple: “If the problem is not enough homes in established suburbs, surely any meaningful solution must involve building more homes in said suburbs?”

“Kohler misses the moment,” they write. “The political mood is changing. There is a growing groundswell of support for more density, and a growing awareness of the costs of locking up vast tracts of our cities from development.”

They are dead right that I’ve missed that. If there is a groundswell of support for more density, it has passed me by, which is clearly a failure on my part. Brendan and Joey say that I am unduly pessimistic, and they are also dead right that I’m pessimistic – about the capacity of Australian politics to deliver difficult solutions about anything, especially denser housing. Unduly so, as they assert? Time will tell. I really hope the men from Grattan are right and I’m wrong, because it’s quite true that “denser cities are more efficient cities,” and that by far the simplest solution to the shortage of housing and high prices would be more medium-density housing close to the city.

To drive home my misfire, Mark Walker persuasively explains the difficulties of fast trains:

It is the convoluted, contour-following nature of the original nineteenth-century track alignment that still largely dictates the speed of trains today. To speed them up, we need to spend big on upgrading the actual line of rail – the embankments, viaducts and cuttings on which the rails are laid . . . The problem is centrifugal force. The faster a train travels, the gentler must be the bends in the track, or the engines and carriages can tip up, and tip over.

So that seals it: fast trains are too expensive and they won’t be needed because the NIMBYs are in retreat. What I wrote in the essay is wrong, it seems, and I couldn’t be happier about that.

Peter Tulip’s complaint is that I put too much weight on the impact of negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount introduced in 1999 – any weight at all, in fact. “There is no credible research supporting this claim,” he writes.

When I began this project, I decided to investigate and explain the housing problem in three steps: first, what happened to house prices; second, what the effect on Australia and its citizens has been; and third, when it happened. I thought the “when” would help explain the “why,” and all these things together would provide the solutions. The “when,” I thought, was evident from the two charts towards the front of the essay of house prices against both incomes and GDP. It obviously happened in 2000.

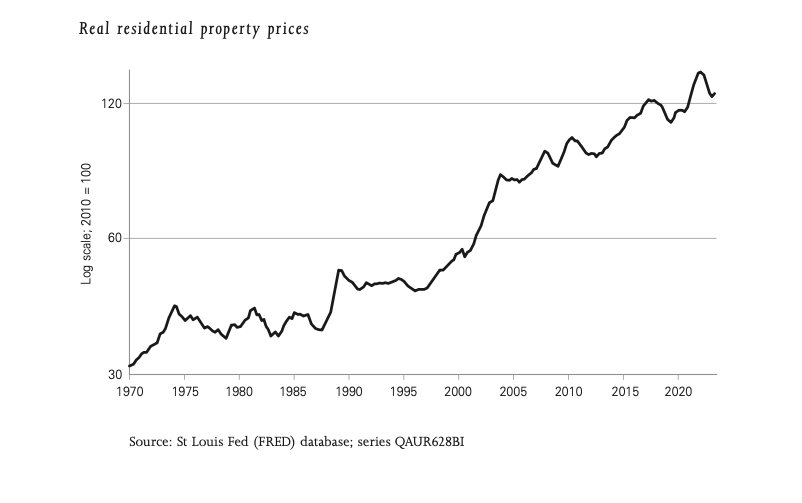

I admire Peter’s work and his expertise, and he says I should have used a logarithmic (log) scale, which would have told a different story: that “an acceleration can be seen [after 2000], but it is not dramatic and it begins before the tax change.”

Log scales are used to show exponential curves because they don’t fit on a graph. I’m not sure why a log scale is needed for house prices. Peter includes a log-scale chart of house prices in his response, which he says shows that house prices started rising before 2000. Well, looking at his chart, it’s clear that prices were broadly flat from 1972 to 1987, jumped sharply between 1987 and 1990, which was the rise “before the tax change” that Peter talks about, were flat again for ten years, and then from 2000 rose rapidly and inexorably for more than twenty years to the present day.

I’m sorry, but I reckon that rise in Peter’s log-scale graph is dramatic, and I just don’t accept that the jump in prices in the late 1980s – which was the property bubble and bust that produced the 1991 recession – rules out the tax reforms of 1999 as an important cause of rising house prices. If anything, Peter’s chart reinforces the point, even without including household incomes or GDP.

Graphs aside, house prices increased at 3 per cent per annum before 2000, the same rate as income, and 6 per cent after 2000, double the rate of income. So I stand by the proposition that the psychological effect of halving the capital gains tax with pre-existing negative gearing deductions had a big impact on demand for houses, and that removing those tax concessions must be an important part of dealing with housing affordability.

But I appreciated the generous efforts of Peter, Brendan and Joey to set me straight, and of course the kind words of many others, including those responses that couldn’t be printed for space reasons. I particularly valued Judith Brett’s historical insights, Nicole Haddow’s millennial viewpoint and Nicholas Reece’s local council perspective.

The process of researching this subject and then engaging with responses to my essay has confirmed that this is a subject about which a lot of people have been thinking deeply and expertly for a long time, and Australia is well served by them. It’s just a pity they are not listened to more. We are less well served by the politicians and bureaucrats whose job it is to do something about it.

Alan Kohler

THE GREAT DIVIDE

Correspondence

Housing is an enormously complex subject, frequently misunderstood by experts and the public alike. Alan Kohler’s insightful analysis navigates through the historical evolution and policy complexities, rightly diagnosing that our challenges have been decades in the making. He is astute in his observation that it’s difficult for governments to act, as housing policy change generally creates losers as well as winners (in any given year, the number of home owners with an interest in high house prices is vastly larger than those trying to get into the market).

But the view that if only governments could muster the political courage to alter some policy settings, this could all be fixed is, sadly, wrong. We wish it were that easy.

The role of government incentives and interest rates can be overstated in their effect on house prices. Over the last twenty years, house prices have grown on average by just over 7 per cent a year, a $7.1 trillion increase. Government policy, in the form of preferential tax treatment and incentives for property assets, is often asserted as the main reason for this growth. However, the Reserve Bank of Australia has published estimates that the capital gains tax exemption and negative gearing combined account for less than 2 per cent of the multi-trillion-dollar recent growth in house prices.

Meanwhile, media commentary typically focuses on the role of interest rates. But property prices increased substantially during the thirty years of rising interest rates after World War II, as well as in thirty years of falling rates after 1990 (and as rates have increased more recently). While both interest rates and tax policies are relevant, they don’t explain most of the growth we’ve seen in Australia over many decades.

So, what is the biggest driver of the growth of house prices over such a long period? We think the single largest thing that is underplayed is the importance of land value.

Land has a significant and outsized role in house prices because it’s not like other things we buy. We all need a place to live, so land is different from the kinds of goods where, if the price gets too high, people can opt out of using it (hence, if necessary, people stop eating out in order to continue to pay their mortgages, rather than the other way around). And, crucially, there’s only so much of it – as Mark Twain put it, “They’re not making it anymore.”

The supply is doubly fixed, given that each parcel of land occupies a unique location. It’s often observed that Australia has an abundance of land. But well-located land – near jobs, public transport, services and amenities – is limited. This, of course, is where most people want to live.

This is a bigger challenge in Australia than elsewhere. Australia has unusually high population growth – only one other country in the developed world has such consistently high growth. Also unusually, Australians are highly concentrated in a few large, low-density cities. Between them, Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane house half the population, the majority living in low-density areas between the CBDs and fringe greenfield developments.

This combination of high population growth and an unusual urban settlement pattern makes well-located urban land much scarcer in Australia than elsewhere. And when a good is scarce, we can expect its value to increase. In our white paper What Drives Australian House Prices Over the Long Term, we have calculated that, driven by land value, residential property now constitutes almost half of Australia’s total national assets.

So while many point the finger at various government policies or inaction as the principal problem, we think the problems are fundamentally structural, rooted in the role of land values. As such, no simple change in government policy can solve them. Given how hard it is for governments to act in this area, that is probably just as well.

On a parenthetical note, it is essential to distinguish between land value and building value. While buildings typically depreciate over time (as wear and tear erode their value, and desirability decreases relative to newer buildings), land, especially well-located land, appreciates due to its limited and scarce nature. Houses and other detached dwellings typically have the major proportion of their value consisting of land value, while high-density apartments typically have a low proportion. This distinction contributes to the varied growth profiles of different property types, with detached dwellings exhibiting the strongest growth, and higher-density apartments typically experiencing the lowest.

What to do? We think the creation of an Australian Housing Fund industry is the real solution.

To have any chance of working at the scale required, solutions need to run with the economics of the Australian property market, rather than against them. The role of land value described above makes Australia a high capital-growth residential property market. It is also, therefore, a lower-yield market, unlike, for example, the US residential property market, which in the main is characterised by higher yields. This means that overseas solutions, such as Build to Rent, which rely on good yields for their returns to investors, run counter to the economics of the Australian property market and are likely not to be attractive enough to make a significant difference.

But a high-growth market also constitutes an opportunity. At the moment, there are only two ways to benefit from the high capital growth available in Australia: owner occupation, and direct property investment through being a landlord. At the same time, high house prices relative to incomes make deposits ever harder to save, locking too many people out of home ownership. They are then stuck in a poorly performing private rental system which works for neither renters nor landlords (the former get poor tenure security and a poor experience, while the latter get poor average returns along with management and maintenance headaches).

The capital growth available in Australia’s housing market – driven by our population growth and settlement structure – means that large amounts of private capital could be mobilised to help solve these problems. In Mobilising Private Capital for Housing Solutions, we argue that a Housing Fund industry could be put to work by using investors’ money to solve two enormous challenges: to help people into home ownership through shared equity; and to give renters security of tenure and a better experience.

Shared-equity models can ease Australia’s housing affordability crisis by allowing homebuyers to purchase property with lower savings for a deposit in exchange for giving some of their home’s equity or capital growth to a third party. Housing funds would provide the capital for shared-equity providers to co-invest with eligible homebuyers. Governments are now offering shared equity in most jurisdictions but we will need private capital to meet needs that are an order of magnitude bigger than governments can fund.

This is particularly relevant for first homebuyers or those who have difficulty saving for the large deposit needed to purchase a home, including those who do not have access to financial assistance from the Bank of Mum and Dad.

Home ownership, even with a mortgage, is the best form of housing security in Australia, with no risk of residency being terminated by a landlord, and numerous protections from banks and governments to help financially at-risk households avoid foreclosure. Home owners also experience a higher quality of experience than renters, facing few restrictions around alterations or renovations, and aren’t subject to inspections, lease contract renewals or disrespectful treatment by poor property managers.

For those who cannot or do not want to own, housing funds would also invest in owning and managing large portfolios of long-term rental properties – a model long established in mainland Europe. These would provide tenants with a security of tenure not currently available in the private rental market, along with a significantly better renting experience. Housing funds could further differentiate themselves by giving tenants guarantees relating to safety, autonomy, flexibility and dignity. Multi-year rental agreements, interior alterations, maintenance request guarantees, high minimum standards on heating and cooling, energy retrofitting and minimum energy-efficiency standards would all be in the interests of the providers as well as tenants. Governments should ensure that the industry is regulated so that only reputable providers are able to operate – lessons should be learnt from the United States, where there is both good and bad provision.

It should be noted that current land tax policy represents a significant barrier to the development of institutional ownership in Australia. Other than in the ACT, under current settings the more land that individuals and corporations own, the higher their land tax rates. Since providers of affordable housing, who rent at a discount to the market, are exempt from land tax, the only current pathway for institutional ownership is as affordable housing providers. This is good for the provision of below-market rentals but means that households in the private rental system would not be able to access the tenure security and improved experience that institutional ownership would make possible.

The almost $10-trillion residential housing market and the growing scale of our housing crises mean that governments alone will never be able to fix them. The capital growth in Australian housing alone is roughly equal in size to the entire federal budget. But there could be a scalable solution through mobilising private capital.

The federal government recently announced a major push to work with superannuation funds to engage with Australian housing, as they currently have very little exposure to Australian residential property despite their substantial size and the magnitude of the asset class. Indeed, when discussing private investment in Australia, most of the discussion, and certainly most policy emphasis, is focused on institutional investors – notably large superannuation funds.

A much larger source of capital lies with landlords, where two and a half million individual property investors between them have over $2 trillion invested in over a quarter of Australia’s residential property market (and, in contrast to superannuation funds, have already chosen the asset class). And, because much of this capital is generating poor returns alongside daily problems for both landlords and renters, it is a capital pool that is ripe for redeployment for better housing outcomes. Corporate, family office and high-net-worth individuals also have an important role to play, particularly in seeding demonstration funds.

Our inspiration for these funds is the creation, forty years ago, of Australia’s superannuation funds, which have revolutionised our post-work lives. The role of superannuation funds is to provide secure dignified retirement. Given the opportunity, housing funds could become the architects of secure dignified housing.

Evan Thornley & Jane-Frances Kelly

THE GREAT DIVIDE

Correspondence

Alan Kohler’s essay is an excellent summary of the key issues which have contributed to Australia’s housing affordability crisis. It is one of the few substantial, lucid analyses to comprehensively consider the contribution of poor policy to both insufficient housing supply and excessive housing demand.

Alan aims most of his rhetorical barbs at the political class – of all persuasions, and all three levels of government, over many decades. In Alan’s narrative, politicians are the primary perpetrators of the problem, as well as the custodians of the solutions.

Politicians do indeed carry a significant share of the responsibility. Alan expertly sets out the perverse political incentives which have discouraged policy change in areas such as tax, land release, zoning and public housing that would have helped to correct (or at least not exacerbate) the crisis. In this area of policy, politicians have had little reason to prioritise all of society at the expense of existing home owners.

But politicians are not wholly responsible. If they were, Australia’s housing pain would be a global anomaly. In some ways it is – Alan makes the point that each country’s experience is unique. But the unaffordability of decent, well-located housing for people of average means is an issue for many countries around the world. And housing is not the only asset class which has become “unaffordable” when using Alan’s preferred metric of price growth consistently and substantially outpacing income growth. From commercial property, infrastructure and the share market to art, wine and vintage cars, the prices of investable assets around the world have exploded over the past few decades. So much so that the phenomenon has in recent years been described as an “everything bubble.”

Why has that happened? It is worth stepping back for a moment to consider how an asset is priced. In financial markets, and with some simplification, the value of an asset is equal to the amount of income it can generate over time. For residential property, that income is the rent paid to the landlord (or the rent that would be paid, for property owned by the occupier). So, setting aside complications such as tax and other expenses, the value of a residential property should be equal to the total amount of rent it can provide the owner from now into perpetuity.

That sounds straightforward enough. But a dollar of rent today is not the same as a dollar of rent tomorrow. Or next year. Or next decade. To be compared with today’s dollars, future rent needs to be “discounted.” What discount rate should be used? Again, setting aside some complications, one relevant benchmark would be the risk-free interest rate, typically considered to be the interest rate on ten-year government debt.

That’s critical, because interest rates (on ten-year government debt, and more generally) have spent the last four decades charting a slow but steady course downwards towards zero. By definition, that downward trend in interest rates has caused the value or price of all assets – including residential property – to be regularly and consistently revised upwards.

The past four decades were special. A number of factors combined to put downward pressure on interest rates: demographic change, the rapid growth of China and other emerging economies with relatively high savings rates, more globally interconnected financial markets and a vast increase in international capital flows, technological change and more complex financial products. As a result, debt ballooned. In the 1970s, the world had borrowed $1.15 of debt for every $1 of economic activity. By 2022, that ratio had more than doubled, with the world having accumulated $2.38 of debt for every $1 of economic activity.

This is the “financialisation” of the economy that Alan makes several brief references to in his essay, but with little elaboration about how this has contributed to the housing crisis. Housing is a unique class of asset. As Alan notes several times, housing should be seen as a basic human right and not a source of wealth creation. Unfortunately, that ship sailed long ago.

What might come next? Interest rates temporarily reached zero during the pandemic. They may not rise substantially from here, but nor is there much room left for interest rates to continue to fall. That does not mean the “everything bubble” will burst. But it will inflate with less enthusiasm in the years ahead, giving aver- age incomes time to make up some ground on house prices.

Ultimately, this is all a matter of timing. Good timing, or bad, depending on your perspective and, quite likely, your age. The issue is not so much that millennials and gen Zs have been dealt a bad hand. Rather, it is that baby boomers (and many gen Xers) won the generational lottery. That may appear to be a false dis- tinction. The point is that the baby boomers are the first, and very likely the only, generation in which an individual of average means can retire wealthy – perhaps even a multi-millionaire – solely on the basis of having owned their own home. That wasn’t possible for any previous generation, and it probably won’t be possible for any future generation.

Just like a surprised lottery winner at the local newsagent, older generations don’t need to feel guilty. But they should at least recognise their good fortune and be willing to share the windfall profits they have accumulated via the tax system. Otherwise, the risk that existing intergenerational inequality morphs into a broader schism in Australian society, as Alan alludes to, is very real.

With interest rates no longer on a downward trend, their contribution to any further inflating of Australian property prices will be muted at most. That means that while politicians are not wholly responsible for the problem, they are wholly responsible for the remaining solutions.

No wonder Alan ends his essay on a pessimistic note. It’s hard to feel anything but.

Stephen Smith

THE GREAT DIVIDE

Correspondence

Just over ten years ago, I gave a talk to a dinner organised by the Henry George League (a small but enthusiastic group dedicated to the ideas promulgated by Henry George, a nineteenth-century economist and journalist best remembered today for his advocacy of a “single tax” on the unimproved value of land), which three months later formed the basis for a submission I provided to a Senate committee enquiry into affordable housing. Both were titled “Australian Housing Policy: Fifty Years of Failure.” If I were to give the same talk again – or write a similar submission to yet another parliamentary inquiry – the only things I would change would be to update the numbers I quoted in it and change the title from “Fifty Years of Failure” to “Sixty Years of Failure.” Because that’s what the policies of governments of all political persuasions, at all three levels – federal, state or territory, and local – have been. An unmitigated failure.

Alan Kohler was kind enough to quote from that talk in his Quarterly Essay. Indeed, Kohler went much further back into history than I did – to the mid-1820s. After reading his essay, I could almost speak of Australian housing policy as entailing 200 years of failure – except for the three decades or so after World War II when, as Kohler documented, Australian housing policy did succeed in meeting its stated goals of increasing home ownership and providing an adequate stock of affordable rental housing for those unable to attain home ownership.

To my way of thinking, one of the valuable contributions which Kohler’s essay makes to the contemporary debate about Australia’s housing crisis is in drawing out the history which shows that governments can – if they make the “right” policy choices – ensure that people can afford to buy or rent a home, even when faced with more rapid growth in the population (and hence in the “underlying” demand for housing) than we have experienced over the past eighteen months.

That is what they did between the end of World War II and the mid-1960s, when Australia’s population grew at an average annual rate of 2.2 per cent per annum (compared with 1.6 per cent per annum over the past twenty years), and the population of Australia’s eight capital cities grew at an average annual rate of 3.4 per cent per annum (because, in addition to the postwar “baby boom” and the massive immigration program, Australians were also moving from rural areas to state capitals in large numbers). Yet despite that, the average price of housing remained unchanged, as a multiple of average earnings, at about 3.5 times: and the home ownership rate rose by 20 percentage points – from 52.5 per cent to 72.5 per cent – between the 1947 and 1966 censuses.

That was possible because governments of both political persuasions, at both the federal and state levels, as well as local governments, focused on expanding the supply of housing and, beyond the bipartisan support for a big immigration program, refrained from adding to the demand for housing. Yes, as Kohler points out, there were ideological differences between the two major parties as to whether public housing should be sold to prospective buyers. But there was a bipartisan commitment to ensuring that the supply of housing matched the demand for it.

As Kohler goes on to show, that commitment began to waver, beginning with the introduction of the first program of cash grants to would-be first home buyers by the Menzies government in 1964. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the home ownership rate peaked at the first census after that and has been declining ever since. At the federal and state levels, governments of both political persuasions have increasingly favoured policies which have the effect of inflating the demand for housing; while at the state and local level, governments have increasingly favoured policies which have the effect of adding to the cost or the difficulty (or both) of increasing the supply of housing.

In my view, history amply demonstrates that anything which allows Australians to pay more for housing than they otherwise would – be it cash grants to first-time buyers, stamp duty concessions for first-time buyers, preferential tax treatment for residential property investors, government guarantees for loans to people who have difficulty accumulating the required deposit, shared equity schemes, lower interest rates, or easier standards for determining loan eligibility – results in Australians paying more for housing, and hence higher housing prices, rather than in higher home ownership rates.

Yet, despite the accumulation of six decades’ worth of history amply demonstrating that point, governments of all political persuasions keep doing the same things – and, echoing Albert Einstein’s definition of insanity – expecting a different result.

Another of Kohler’s valuable contributions is to point out why. As he says, “housing is a cartel of the majority, with the banks and the developers helping them maintain high house prices with the political class actively supporting them. Everybody involved in this game – homeowners, banks, developers and state and federal politicians – wants house prices to rise for their own reasons.”

I’d put the same point slightly differently. Over the past thirty years, there have been, on average, about 112,000 first home buyers in any given year. Up until the moment they sign their purchase contracts and draw down their mortgages, they (presumably) want governments to do things that would restrain the rate of increase in property prices. But at any point in time, there are more than 6.2 million households – which probably means at least 10 million individuals (out of 17.7 million on the electoral roll) – who own (individually or with a spouse or partner) the dwelling in which they live – all of whom have a vested interest in governments doing things that boost the rate of increase in property prices.

One thing that successful politicians can do is to count votes. And they know that there are far more votes to be had from people who want property prices to keep going up than there are from people who want them to stop going up, or even to go down. And that, I’ve come to believe, is the real reason why what Kohler calls “Australia’s housing mess” will probably never be cleaned up by government policies: because a majority of voters don’t want it to be cleaned up. And politicians know that.

Saul Eslake

THE GREAT DIVIDE

Correspondence

In his engaging, avuncular style, Alan Kohler lays out the drivers of Australia’s housing mess with admirable clarity and emphasises its profound implications for inequality and social mobility. I have already sung the praises of The Great Divide in a review for Inside Story. Here, I want to pick at one of the knots Kohler identifies: the challenge of “the missing middle.”

This phrase refers to the lack of medium-density dwellings – three- to four-storey apartment buildings that could offer a midpoint between the high-rise residential towers sprouting up in our city centres and the detached houses that continue their outward march on the urban fringes.

The concept of the missing middle can also be applied geographically to indicate the lack of significant new construction in middle-ring suburbs. This is evident in the Albanese government’s desire to see 1.2 million “well-located” new homes built over five years, where “well-located” is code for close to shops, transport, jobs and services. In other words, the federal government wants new homes to be constructed in established suburbs and to utilise existing infrastructure. Yet urban infill is easier said than done. The roots of the challenge lie in the fragmented pattern of land ownership set in place as our cities grew.

As Kohler writes, in the post-war decades, our cities spread rapidly outwards from their dense nineteenth-century centres as the combination of affordable cars, near full employment, mass migration and available land induced families to build freestanding homes on large plots. The great Australian dream was born and locked in a sprawling urban form that is resistant to change. Once you’ve constructed neighbourhoods this way, asks demographer Simon Kuestenmacher, “how do you add medium density?”

Kuestenmacher’s crucial question takes Kohler to “the problem of state and local governments and their control of housing supply through zoning.”

There is no doubt that planning and zoning regulations can be a barrier to building denser housing in established neighbourhoods. Principle 4 of the Brisbane City Council’s “Future Blueprint” is “protect our backyard,” yet the Queensland government’s vision for shaping south-east Queensland foresees that 94 per cent of Brisbane’s additional housing will come from “consolidation” within the city’s existing urban boundary rather than from “expansion” beyond it. The contradiction between these two objectives set by two different levels of government is glaring.

The problem is not confined to the Sunshine State. The aspiration in Plan Melbourne is for 70 per cent of new housing to 2050 to be constructed in established suburbs and just 30 per cent in expanding greenfield developments on the metropolitan fringe. Other capital cities have similarly ambitious targets for urban consolidation, and, like Melbourne, most are falling well short of meeting them.

There are inevitable tensions between local-level decision-making and an overarching metropolitan strategy. Existing residents can reasonably expect to have a say in the future shape of their neighbourhoods and to resist their leafy greenness being steamrolled to meet state planning targets. Yet hyper-localism can also thwart the rational reorganisation of our cities to accommodate growing populations, adapt to a changing climate and contribute to a low-emissions economy.

The conventional response to the pressing problem of the missing middle is to identify planning and zoning as barriers to building more homes, and to see their removal as the pre-eminent solution. The property industry consistently argues that deregulation is the answer to our housing woes because it will free up the market, allowing developers to increase supply and bring down prices. Yet as Kohler points out, developers only build when they can make a profit. In November 2016, a seventy-storey tower with a hotel and 488 apartments was approved on the block adjacent to my apartment in Melbourne’s CBD. Seven years later the only “development” has been that the site was sold for a massive capital gain. The City of Melbourne endorsed the new owner’s revised plans, and construction was supposed to commence in 2022. There’s still no sign of any work. Meanwhile, a five-storey building sits empty.

Planning constraints may inhibit construction, but their removal does not automatically prompt building. The longstanding quest to unlock residential development by streamlining regulation has so far generated meagre returns, with significant reforms to planning regimes making no appreciable dent on real estate prices. The response is to double down: if housing is too expensive, then that means there’s not enough housing being built, so our deregulation efforts are insufficient and we must deregulate even more. This relentless focus on housing supply blends out any discussion of housing distribution and distracts from other core issues like tax settings.

Still, planning reform now looks set to ramp up another notch as state governments threaten to override more local council powers and amend planning regimes. In future, proposals to replace free-standing family homes with rows of townhouses or to build granny flats to backyards are likely to get swifter, simplified approvals. While this will increase density, such piecemeal infill is likely to erode the amenity of established suburbs, without providing either the scale or quality of housing we need.

In October, at a webinar run by SGS Economics & Planning, SGS principal and partner Patrick Fensham argued that achieving a 70/30 split of new housing between existing suburbs and greenfield projects means building 600 to 700 dwellings per week within current urban boundaries. To date, where this type of residential construction has occurred, he says, it’s mostly taken two forms. First, there’s the conversion of former industrial land into housing – Melbourne’s Docklands is an example – but opportunities to redevelop such “brownfield” sites are becoming scarce. Second, there is residential intensification around “activity centres,” particularly major transport hubs and shopping centres. Melbourne’s Box Hill and Sydney’s Ashfield are examples, though, as Fensham says, these are high-rise clusters, not medium-density housing.

The opportunity yet to be grasped lies in the “greyfields” – the freestanding family homes and backyards of middle suburbia. Much of this housing is reaching its use-by date in terms of energy efficiency, thermal comfort and maintenance costs. It was designed in an era when a family with two or more kids was the dominant demographic typology. Today, with smaller families, and more single and couple-only households, we need different dwelling types. Fensham argues that the old suburban lot must be the building block for the future. It is on these “greyfields” that new, denser, greener and more affordable housing can be constructed. Yet this poses a fundamental challenge, because a single suburban lot is too small to accommodate the quality, midrise housing that constitutes the missing middle. If we are going to meet our 70/30 aspirations, we need first to overcome the fragmented pattern of land ownership established in post-war subdivisions.

In The Art of the Engine Driver, the first of his award-winning Glenroy series, novelist Steven Carroll chronicles family life on Melbourne’s edge in the 1950s as new suburbs were stamped out of farmland. Today Glenroy is middle ring and ripe for redevelopment – in fact, despite planning and zoning constraints, ad hoc redevelopment is already happening. In his webinar presentation, SGS’s Fensham used Glenroy to provide a compelling illustration of how established neighbourhoods might be reimagined, and the opportunity that will be lost if we continue our present trajectory.

Fensham took a sample block of twenty-six lots bounded by four streets. The original subdivision was characterised by detached houses with big backyards. Less than 20 per cent of the land was covered by buildings, an extensive tree canopy cooled the landscape and deep soils absorbed the rain. A first phase of redevelopment saw some of these freestanding houses replaced by single-level semi-detached villa units, two or three to a lot. Next came double-storey semi-detached townhouses, and more recently, rows of double-storey attached townhouses, with as many as five dwellings squeezed onto a parcel of land. If business continues as usual, then before long the block’s original twenty-six houses will have been replaced by ninety-one dwellings. This would constitute a significant increase in density, but at the cost of almost all tree cover and with the old backyards given over to buildings. What little open space remains will generally be buried under concrete.

Fensham offers an alternative vision for coordinated redevelopment in which those twenty-six separate lots are amalgamated into larger parcels of land to enable the construction of 165 European-style medium-density dwellings. This would achieve much greater housing density than piecemeal infill, yet the building foot- print would only take up about 40 per cent of the total land area, leaving plenty of open space for pocket parks, gardens and trees.

It is a much more appealing prospect for suburbia than the hot, hard, unforgiving landscape that will result from the business-as-usual approach to urban consolidation, in which houses are knocked down and replaced one by one. But achieving a denser, greener future will require, in Fensham’s words, “a much more interventionist role” for the public sector to assemble land, master-plan sites and, potentially, constrain developments that won’t achieve the desired densities or which would destroy the existing amenity of trees and open space.

So our key housing challenge is not to get government out of the way so business can get on with rebuilding middle-ring suburbs; it is for government to more actively assist developers to amalgamate sites and reconfigure entire precincts, while engaging with residents to allay their fears and realise their aspirations.

Planning should not be the barrier to building the housing we need, but the enabler.

Peter Mares

THE GREAT DIVIDE

Correspondence

Alan Kohler’s Quarterly Essay, The Great Divide, challenges the assumption that Australians actually want to fix housing affordability and supply, given that a quiet majority arguably hold a vested interest in the status quo. Assuming we genuinely want to bring about changes which promote both home ownership and housing affordability, I argue that this should be tackled in the form of a regional renaissance.

Australia’s biennial intergenerational reports regularly prosecute the case for swelling the resident population to 40 million and beyond through ongoing net immigration. We’re on a course which, if pursued, realistically means that affordable homes in landlocked Enmore or Erskineville simply won’t be achievable. Logically, a change of focus is therefore required. The COVID-19 pandemic unexpectedly presented a remarkable window for employees to demonstrate the ability to work productively and flexibly from home, or closer to home. We should embrace this opportunity to create a broader vision for dynamic regional living.

Of course, economists will justifiably argue that the major capital cities have certain unique benefits in terms of economies of scale, concentration of skills, frequency of interactions, and the potential for serendipitous events. This is all incontestably true. But instead of trying solely to work out how we can cram twenty million people into Sydney, Melbourne and south-east Queensland’s narrow coastal strip, perhaps we should create a grander and more enlightened vision for dynamic and thriving regional cities?

Let’s start with, say, Albury-Wodonga, Bathurst, Dubbo, Orange, Port Macquarie and Wagga Wagga in New South Wales, as well as Ballarat, Bendigo, Mildura and Shepparton in Victoria. In Queensland we have Bundaberg, Cairns, Gladstone, Mackay and Rockhampton, for example, and in Western Australia Albany, Bunbury, Busselton and Geraldton. Add in Tasmania’s Launceston, plus the already-popular peri-urban conurbations within a two-hour sweep of the larger capital cities, and here we have several dozen regional cities and centres which can be the thrust and heartbeat of a dynamic, productive and prosperous Aussie economy. Where people can have space, quality of life and affordable housing.

Australia has been accused in the past of being lucky and lazy, of running face-less and fattened oligopolies, of enjoying the fortune of vast mineral resources, while being a relatively favoured destination for global capital and wealth. The Mittelstand economies of Germany, Austria and Switzerland have variously demonstrated how we may be able to promote geographical diversity, driven forward by growth in nimble and adaptive small-to-medium enterprise (SME) businesses with a global niche, and a focus on technology and excellence. The edge in SME businesses over the big end of town can be in faster decision-making and elite customer service, offering a more human experience.

Life can be challenging for small businesses in a high-cost economy, with Mittelstand economies sometimes encouraging cooperatives or partnerships. SME businesses can excel by doing one thing really well, while working collaboratively with innovative technologies and AI to deliver innovation, entrepreneurship, outstanding training and apprenticeships, and quality customer experiences, with strong regional ties. Craft trades, machinery, electronics, chemicals, automotive parts and a raft of services industries can all fit the bill for growth.

More years ago than I would like to remember, I had some experience of living in Germany when I studied there in the Oberstufe. Germany has had its own housing market and other challenges in recent years, fuelled in part by shifting migration trends and in particular a dozen years of ultra-low interest rates, although house prices notched a record decline in 2023.

My best memories of Stuttgart – today a safe and flourishing city of 600,000 people with its vast sporting stadium, outstanding universities and growing start-up culture – might broadly fit the vision. You can live in the hills five or six kilometres from the heart of the city, with suburbs and villages populated by small business owners and workers in sectors ranging from engineering to personal services. Granted, home ownership rates are not high in Germany. Tenant-friendlier markets lead many to actively opt for long-term leases, enjoying an outstanding quality of life, while taking pride in business expertise and excellence. There could be something worthwhile to learn from this.

There may also prove to be some productivity challenges associated with more Aussies working from home (or perhaps closer to home, in serviced office hubs and not always in the central business districts). Many of the key market players in realty have a material stake in the large commercial office towers, but ultimately floor space will fill up over time, given the projections for population growth.

In Australia, our respective levels of government will need to invest in regional infrastructure – perhaps funded via land value capture – including in transport, educational facilities and healthcare. Why can’t we live in Townsville or Toowoomba instead of cramming into Brisbane’s northside mortgage belt? We’d need to see more appealing employment options and shopping hubs; high-speed internet and connectivity; great schools; road, rail and airports; healthcare excellence; leisure; and attractive housing choices. We need to create a vison, buzz and excitement, and a sense that “Hey, something is really happening here.”

Incentives such as tax breaks and special economic zones can bring all the usual political challenges associated with the picking of winners, but why can’t the Gold Coast be our regional technology hub, with Adelaide specialising in healthcare R&D, and, say, the Pilbara firing up as a leading renewable energy region? Australia is set to experience an array of booming industries ahead, including in green energy and energy security, niche manufacturing, food, healthcare R&D, construction techniques, mining, IT and other modern technologies besides.

Immigration and labour market settings are hotly contested, especially following the snap-back in arrivals as the international borders reopened, but there should clearly be a focus on upskilling the incumbent population, as well as importing more people. In professional services, it has for too long been the case that managers and directors are often imported rather than homegrown. More apprenticeships and vocational training would be a welcome reform, with higher education teaching our required skills and vocations, and not functioning so much as visa factories for international students.

Zoning reform in the capital cities has a key role to play in the housing conundrum; but equally rezoning doesn’t fix everything. I recall living close to Newstead, in inner Brisbane, around a decade ago as a vast swathe of apartment towers began to mushroom out of the ground. The large oversupply of Brisbane apartments was even called out in the Reserve Bank of Australia’s Financial Stability Review as a systemic risk for the economy. The idea that only half a dozen years down the track we would be debating the need for rezoning due to there not being enough development sites would have seemed absurd at the time.

What happened? Concerned consumers stopped buying new apartments, developers put up the shutters and sold off their surplus development sites, and as advertised rents declined the vacancies gradually filled up. Today we are back in a shortage, but by 2026 or 2027 that will quite likely have reverted to a supply overhang. No doubt there could be short-term uplift from rezoning, and overall it would be beneficial to housing supply over time. But over the long run supply and demand tends to revert towards equilibrium, so rezoning is one part of the housing solution, not the miracle cure.

A contemporary example to illustrate the point might be Hamilton Northshore in Brisbane, which can potentially absorb up to 25,000 people in 14,000 apartments, being a large, flat strip of land, effectively ready for development. Why has this supply not all built through the past cycle? Because the cycle was killed by oversupply, high vacancy rates, sliding prices and presales drying up.

There is little speculative building in Australia, and generally speaking new housing will only be built when it is profitable and viable to do so. House prices reflect both demand and supply, and the equilibrium price will occur at the level that matches current demand to available supply. In the short run, supply is increasingly relatively inelastic, given that we have more medium-density construction in the capital cities these days, and that it can take several years to bring new apartment projects to market.

Fixing the rental market is another challenge to be overcome. Tenants’ rights have improved, but the other side of that coin is that there is less protection for landlords than there once was. Many private landlords would doubtless like to offer longer-term leases, but since it’s sometimes difficult to evict even the most problematic of tenants, we are likely stuck with six- or twelve-month leases as things stand.

The burgeoning build to rent (BTR) sector can be a part of the housing solution for the capital cities, but it is also not the whole solution. The UK experience, centred in London, has been mixed. Total returns for the sector over the past half-decade have been modest rather than compelling, even including capital growth. If we take the risk-free rate to be the ten-year bond yield, this has been tracking at around 4 per cent. In Australia we have been assessing BTR portfolios on compressed cap rates of around only 4 to 5 per cent. Will the BTR sector deliver affordable rents? It’s doubtful, given the institutional imperative and the required returns.

Overall, there are numerous challenges ahead for Australian housing market dynamics, dwelling supply and affordability. But with a relative shift in focus from the metropolitan melee to a regional renaissance, they needn’t be insurmountable. We’ve seen a rush to the regions during the pandemic “race for space.” Next, we need to champion a regional powerhouse campaign. The time to plan and invest is now!

Pete Wargent

THE GREAT DIVIDE

Correspondence

Alan Kohler’s Quarterly Essay, The Great Divide, makes an important contribution to the hotly debated issue of Australia’s housing mess. In an erudite and entertaining style, Alan navigates the history of policymaking and politicking that has led Australia, of all countries, to have a shortage of houses.

Alan’s analysis is at its best when exploring the economic drivers of the housing crisis and the role of the taxation system and misguided government grants programs. However, his analysis of the planning system and the critique of state and local government misses some key points and requires a response.

For the last six years, I have served as a councillor and deputy lord mayor at the City of Melbourne and observed closely the way the planning system, local politics and developer activity impacts on the housing market.

The “simple lie” being told is that the housing mess is caused by local councils pandering to NIMBYs by not approving new residential development. The “complex truth” is that many other factors cause the housing supply shortage.

Most local governments in Australia assess planning applications within the statutory time limits and are pulling their weight when it comes to approving new residential development. A recent study by SGS Economics found that, on average, the planning system in Victoria approved about 38,000 multi-unit dwellings for development statewide – more than enough to meet demand. Further analysis by the Municipal Association of Victoria shows planning permits have been approved for 120,000 dwellings, but construction has not commenced.

In the City of Melbourne, I often describe us as a YIMBY council. There are currently well over 100 residential development projects with 22,000 dwellings for which we have given planning approval but which have not commenced. This is the equivalent of half of all the new homes Victoria needs in the next year in one municipality.

Poor, politicised or dodgy planning decisions rightly receive a lot of scrutiny and criticism. There is certainly scope for improvement in planning processes. But that should not take away from the fact that councils effectively facilitate massive amounts of development every year. And they do this with high levels of community input embedded in the process. That community involvement is in turn an important factor in maintaining confidence in the system. I happen to think it also leads to better decisions, at least most of the time.

This highlights the real and complex causes of the problem. As Alan says so succinctly, in Australia “governments don’t build houses, developers do.” And developers will only build projects where they are confident they can make a dollar. In the current market, developers are not starting construction because building and materials costs are sky-high, interest rates are up, insurance costs are soaring, and a spate of building company closures is creating project risk. State governments around Australia have also embarked on a record-breaking infrastructure spend. To be fair, much of this is catch-up after decades of underspend. But they are trying to squeeze a thirty-year pipeline of new infrastructure into ten years. The result is major skills and labour shortages for the residential building sector and overheated construction costs. When developers run the numbers over a new residential project in Australia, they just can’t make it stack up. As a result, Australia is suffering from historic lows in new dwelling commencements, right at the time when demand is high and new supply is needed most.

Kohler also turns his analysis to the vexed issue of land supply and the locating of new residential development with good amenity, especially transport links to employment centres. He writes that “significantly increasing the density of housing within 10 to 30 kilometres of Australia’s CBDs – which is what is required – is going to be difficult, if not impossible.”

This overlooks the fact that most Australian capital cities have significant “growth areas” that exist relatively close to the CBD or along major transport corridors. Due to the good work of city planners in earlier times, Australia’s capital cities are blessed with large tracts of land that have been used for industrial, port, aviation, rail and other uses. These areas could be converted into medium- to high-density residential and mixed-use areas for millions of Australians.

In recent decades we have seen the conversion of old industrial areas into new residential suburbs, such as Docklands in Melbourne and Green Square in Sydney. In Melbourne alone, old industrial areas such as Fishermans Bend, Lorimer, Arden and Macaulay have been designated as “renewal areas” which will be transformed into residential and employment precincts. Add to this Port Melbourne, Footscray, Cremorne and in future years Dynon and Docklands (E-Gate), as well as former industrial areas in Brunswick, Preston and Coburg and other inner and middle suburbs. These areas could house up to 1 million extra people.

A second major opportunity is available along existing train and tram lines and, in some instances, even major arterial roads where there is a first-rate bus service. Rezoning of height and density limits along these transport corridors will provide the opportunity for large numbers of people to live in good locations that are well serviced by transport. The precincts around major railway stations within the existing rail network provide the perfect location for these new medium-density suburbs. Tram corridors close to the city also are well positioned to accommodate more residents along their routes. In Melbourne alone, another 1 million people could be accommodated in these “transport growth corridors” within the existing metropolitan boundaries.

Alan Kohler also flags the brave and sensible idea of utilising the land assembly powers by state and local government. Converting many low-density suburbs to moderate medium-density is hard. Currently we are seeing scores of large single suburban blocks being converted into rows of units with a gun-barrel driveway. Robin Boyd would be turning in his grave at this latest addition to the Australian Ugliness. From a design perspective, the outcome is hideous. Land assembly can help overcome this problem by aggregating multiple blocks, which can then be master planned and developed to deliver high-quality, well-designed medium-density housing. The land assembly activity should be focused on areas close to railway stations and transport hubs. The politics of land assembly is obviously challenging. But in recent times, state governments have proven to be very brave and very good at undertaking land assembly activities when delivering major new trans- port projects and hospitals. It is time to turn this activity to housing.

A final small but important idea. New design rules and thinking for housing could also deliver improved affordability. For example, apartments built for the investor market have a bathroom for every bedroom. But this is not needed for apartments where people are planning to live long-term. Design rules could also make better use of communal spaces, delivering smaller and more affordable apartments that have larger communal areas and features such as a shared laundry on each floor. Through clever design thinking we can cut the cost of housing construction while still delivering high-quality homes.

Nicholas Reece

THE GREAT DIVIDE

Correspondence

Public discussion of housing policy suffers from undisciplined eclecticism. Too many commentators provide long, unstructured lists of multiple causes or conclude that the truth lies between competing explanations. This muddle reflects an inability or unwillingness to distinguish the important from the unimportant. Alan Kohler’s The Great Divide and the accompanying media coverage are examples.

Instead, let’s be clear. Housing costs are high and rising because growing demand interacts with unresponsive supply. This has been going on since at least the 1970s. Rising demand in turn reflects higher population, higher per-capita income and (since their peak in the 1980s) falling real mortgage rates. Taxes are not an important factor.

Unresponsive supply largely reflects zoning restrictions. If the housing market worked like other consumer goods markets, higher demand would have resulted in many more dwellings. Instead, restricted supply has resulted in soaring prices.

Alan Kohler gets much of this right. His analysis of the dimensions of the problem and how it is ripping the social fabric apart is readable and incisive. And his discussion of zoning restrictions is spot-on. As he notes, zoning is estimated to have raised the price of housing in our biggest cities by hundreds of thousands of dollars. Those estimates are in line with an enormous body of research. (Full disclosure: Kohler cites my research on zoning approvingly.)

Kohler covers a wide range of other issues. I confine my comments to my biggest concern: his overemphasis of tax concessions. He argues that the interaction of negative gearing with discounted capital gains taxes is a major reason housing is unaffordable.

There is no credible research supporting this claim. On the contrary, good researchers have estimated the effect of negative gearing and capital gains tax concessions on housing prices using different approaches and repeatedly found this effect to be tiny. John Daley and Danielle Wood compared the revenue cost of the concessional treatment of capital gains tax and negative gearing to the value of the housing stock – and on that basis estimated that the tax concessions may boost the level of housing prices by 1 to 2.2 per cent. Gene Tunny, using a similar methodology and assumptions as Daley and Wood, found larger impacts of up to 4 per cent on house prices on average. The most detailed study is by Yunho Cho, Shuyun May Li and Lawrence Uren. In a micro-founded model, they found that removing negative gearing would reduce house prices by 0.9 per cent and raise rents 2.5 per cent. Deloitte Access Economics estimated the ALP’s 2019 policy of restricting negative gearing to new housing and reducing the capital gains discount would reduce established dwelling prices by 4.6 per cent and new dwelling prices by 3.6 per cent. Effects of only eliminating negative gearing would be smaller.

In summary, negative gearing and the capital gains discount are estimated to boost house prices between 1 and 4 per cent, while having a smaller negative effect on rents. Most of these estimates represent a long-run “one-off” effect that would have been incorporated into housing prices decades ago.

It does not require technical research to see that the tax concessions are unimportant. Kohler points to the acceleration in prices after capital gains were discounted in 1999. However, the logic of that argument would imply that prices should have fallen by twice as much following the introduction of capital gains tax in 1985. Instead, prices rose. Taxes on investor housing were much lower in the early 1980s but prices were lower.

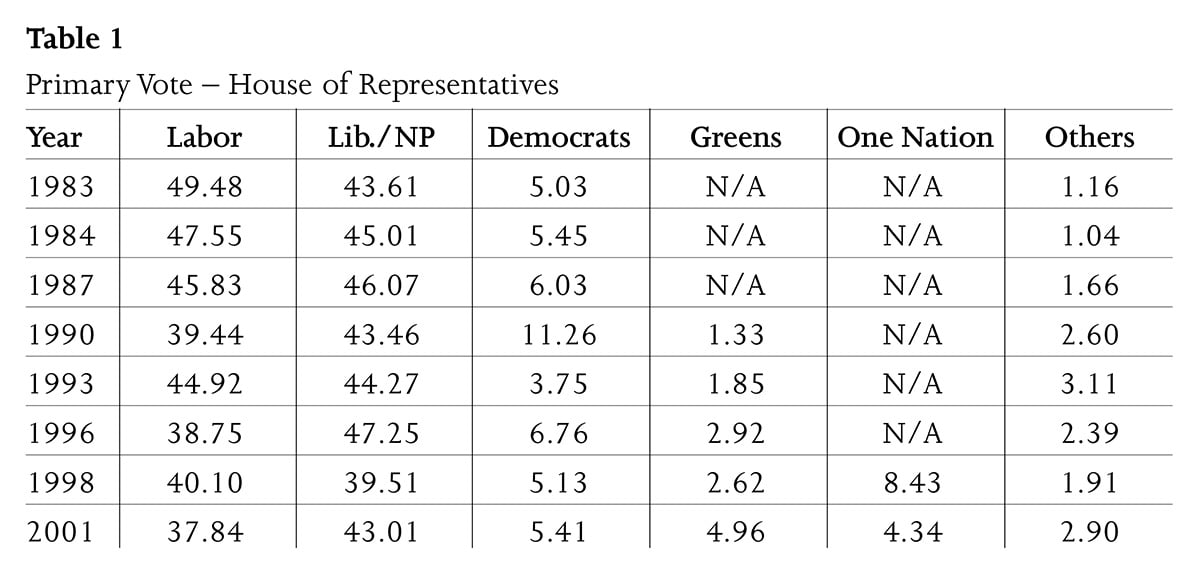

The evidence Kohler provides for a large effect of the tax concessions is a chart showing housing prices accelerated after 1999. That chart uses an arithmetic scale, which exaggerates the change. If instead one plots house prices on a log scale – as is standard for variables subject to exponential growth – an acceleration can be seen, but it is not dramatic and it begins before the tax change.

Empirical studies of housing prices, such as my 2019 paper with Trent Saunders or more recent work by Peter Abelson and Roselyne Joyeux, attribute the faster recent growth to lower real mortgage rates and higher immigration. They give no role to tax concessions.

The fundamental problem underlying the housing crisis is that voters oppose more housing in their neighbourhood because they don’t know – or don’t care – about the harm this opposition does. That needs to be explained to them. Kohler’s discussion of zoning restrictions and their effect on Australian society is very good in this respect. However, public education also requires paying attention to the research and not being distracted by unimportant side issues.

Peter Tulip

THE GREAT DIVIDE

Correspondence

In The Great Divide, Alan Kohler correctly identifies a singular lack of mass public transportation, such as rail, as one of the reasons for the urban sprawl that blights our cities. He also questions why more of our regional centres have not developed as commuter cities, featuring more affordable housing, as is the case in Europe.

It is largely due to the well-known tyranny of distance that fewer rail lines were built either out of our major centres, or between secondary centres that were able to establish themselves regionally. Of those that were, many closed once motor transport became dominant, unable to compete with the speed and convenience of trucks and cars, which could utilise gearing and the grip of their rubber tyres to climb steep hills, whereas trains were limited to very gentle gradients due to the lack of grip between steel wheels and rails. This traction limitation required rail lines to closely follow the contours of the land, while budgetary constraints prevented them sweeping majestically across valleys on expensive viaducts, or ducking into even more expensive tunnels to avoid mountains, making them longer and more winding than is today ideal, and therefore much slower.

It is the convoluted, contour-following nature of the original nineteenth-century track alignment that still largely dictates the speed of trains today. To speed them up, we need to spend big on upgrading the actual line of rail – the embankments, viaducts and cuttings on which the rails are laid.

Why can we not simply purchase faster trains? The problem is centrifugal force. The faster a train travels, the gentler must be the bends in the track, or the engines and carriages can tip up, and tip over. Queensland Rail attempted to overcome this by using the famous “tilting trains” that use hydraulics to “tilt” the mass of the carriage towards the inside of the bend, thus enabling higher speeds and shorter travel times. But they are still limited to around 160 kilometres per hour, and only on a good day on a well-maintained track!

Very Fast Trains capable of 350 kilometres per hour, such as Japan’s Shinkansen and France’s TGV, require track with very low radius bends to achieve their much higher speeds. The track bed also needs to be utterly stable, which often requires specialist engineering, costly maintenance regimes or additional concrete reinforcing, especially in the acceleration and deceleration zones near stations.

Yet some countries have been able to establish a Fast Rail network that uses less expensive construction techniques and slightly slower rail stock. Spain, for example, with double our population yet only a tenth the area – with distances between major centres much shorter – has been able to develop Europe’s longest Fast Train network (the Alta Velocidad Española, or AVE) comprising 3200 kilometres of its total 16,000 kilometres of rail, servicing all its major cities. Spain’s AVE takes approximately three hours to travel the 450 kilometres between Madrid and Seville, equating to a six-hour trip between Sydney and Melbourne, using fully electric Fast Trains capable of 200 kilometres per hour. Had we similar Fast Trains – and straighter line of rail – here in Australia, it would be possible to commute from Sydney to Canberra, or Albury to Melbourne, in under two hours.

The other difficulty is that freight provides the main revenues for train line operators, not passengers, and the current thinking on this subject is to stick with diesel locomotives hauling double-decked freight wagons (as on the Melbourne to Brisbane Inland Rail Project). A continuing focus on this methodology could preclude electrification, as the upper container on a double-deck wagon would foul the gantries holding the power lines for the single-deck passenger and bulk-freight trains.

However, there is an argument for the electrification of inter-city rail, as part of our commitment to meeting carbon emission reduction targets, that could, eventually, lead to both cheaper and less polluting freight transportation, as well as faster passenger rail, and to the revitalisation of regional centres. Road freight accounts for 16 per cent of our overall carbon emissions. Rail, by contrast, produces only 4 per cent of total emissions, and this while utilising existing diesel-powered trains. Ideally, we should seek to electrify our rail network, reducing emissions to near zero, then move much of the road freight onto rail, to further reduce carbon emissions from transport, and making the rail lines more profitable.

If rail was electrified, especially with renewable energy drawn from regional renewable projects, it might also make sense – as a “nation-building” exercise – to straighten, realign and reconfigure our major inter-city train lines to enable the faster point-to-point times that would in turn enable regional centres to develop as commuter cities, as so many have in Europe.

The only previous serious attempt at decentralisation, noted by Kohler, was initiated by the Whitlam government fifty years ago. The resultant “growth centres” pioneered in the 1970s are today thriving regional hubs, largely self-supporting in terms of industry, employment and (relatively) affordable housing.

Perhaps it’s time to revisit decentralisation – via rail realignment, electrification and implementation of Fast Trains? Such a policy would enable real population growth outside the major cities, putting downward pressure on housing costs nationally, while also achieving significant reduction of carbon emissions, enabling us to better and more quickly reach our emissions targets.

Mark Walker

THE GREAT DIVIDE

Correspondence

Alan Kohler’s The Great Divide is a compelling account of Australia’s housing calamity and how it threatens to tear our society apart. Within living memory, Australia was a place where housing costs were manageable and people of all ages and incomes had a reasonable chance to own a home with good access to jobs. But the great Australian dream of home ownership is rapidly turning into a nightmare for many young Australians, while the growing divide between the housing “haves” and “have nots” risks returning Australia to the Jane Austen world of the late-eighteenth century.

Kohler correctly diagnoses the core driver of unaffordable housing: it’s too hard to build more homes in established suburbs where people want to live. But having done so, he veers regrettably off-course to propose solutions that have little chance of working, and which simply act to distract his readers from the main game of building more homes. Kohler misses the moment. The political mood is changing. There is a growing groundswell of support for more density, and a growing awareness of the costs of locking up vast tracts of our cities from development. With momentum building and much more still to do, Kohler’s misfire is particularly unfortunate.

Historically, Australia has not built enough housing to meet the needs of its growing population. Heading into the COVID-19 pandemic, Australia had just over 400 dwellings per 1000 people, which was among the least housing stock per person in the developed world. Australia had also experienced the second-greatest decline in housing stock relative to the adult population over the twenty years leading into COVID, and Australian cities are some of the least dense in the developed world.

The reason is simple. The frameworks and processes that dictate what gets built where are hugely biased against change. Older and wealthier residents of well-located suburbs – those who prefer their neighbourhoods to stay the same – get an outsized say. Prospective residents, who might live in new housing in desirable suburbs were it to be built, find themselves effectively unrepresented.

The result is “missing middles”: hectares of prime inner-city land, close to jobs and transport, rising barely taller than two stories. The flow-on effect is high prices and rents, a stagnating economy because fewer people can live close to jobs, and expensive and environmentally damaging sprawl into farmland and floodplains.

If the problem is not enough homes in established suburbs, surely any meaningful solution must involve building more homes in said suburbs? But Kohler is unduly pessimistic, arguing that more medium-density housing is “going to be difficult, if not impossible,” “won’t work,” and “will never actually happen.”

Kohler contends that addressing the supply problem directly is too hard, and instead searches for alternatives that have little prospect of succeeding. He does this because he judges that the obvious answer – building more housing in the inner- and middle-ring suburbs of Australia’s major cities where most Australians still want to live – is politically unworkable.

Kohler frames NIMBYism and heritage restrictions as “natural barriers” to greater density. But there’s no natural law that says we must let the aesthetic preferences of existing residents for Victorian terraces or Californian bungalows trump the needs of their fellow Australians to have somewhere to live. The restrictive zones in desirable suburbs are not unalterable commandments handed down like ancient laws. Building denser cities is a political decision, and Kohler misses that the political tide is starting to turn.

Until recently, supply-side reform was an obsession for a passionate few, but largely absent from broader political discourse. But in recent times, the political clout of renters has grown and the YIMBY movement has gained momentum. Sacred cows are slowly being slaughtered. The Minns government in New South Wales has plans to up-zone large amounts of well-located land, including overriding heritage controls where they conflict with more density. Victoria is aiming to build 800,000 homes over the next decade, with at least 70 per cent in established suburbs. The Albanese government has put $3.5 billion of federal money on the table, mirroring a Grattan Institute recommendation, to push the states to help build 1.2 million homes over the next five years. This isn’t just an Australian phenomenon. Similar shifts are taking place in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom and New Zealand. Kohler has misread the political winds.

Key to this change is the fact that most residents of Sydney and Melbourne actually want more density if it means being able to live in a better-located suburb. Denser dwellings – townhouses, apartments, etc. – made up 44 per cent of Sydney’s housing in 2016, and 33 per cent of Melbourne’s. Yet a Grattan Institute survey showed that residents say they actually want those numbers to be 59 per cent in Sydney and 52 per cent in Melbourne.

The weight of evidence is becoming impossible to ignore. Take New Zealand: in 2016, Auckland – a city of 1.5 million – rezoned about three-quarters of its suburban area to allow more intensive land use. Researchers found that this led to a doubling of the city’s rate of housing construction. Unsurprisingly, rents in Auckland are lower now – relative to inflation – than they were in 2016, whereas rents across the rest of New Zealand have gone up by 10 to 15 per cent over the same period.

Denser cities don’t just offer cheaper housing. Done well, they also bring amenity, vibrancy and walkability; certainly, much more so than a satellite suburb fifty kilometres from the CBD. Several cities with similar populations but higher densities – such as Vancouver, Toronto and Vienna – outrank Sydney on quality-of-life measures.

But Kohler argues land-use planning reform is too hard, preferring an alternative approach: run faster trains to peri-urban and regional areas, massively increasing the commutable distance to our major cities. This would be unfair, costly and ineffective. Allowing more homes in desirable suburbs would enable more young Australians to live, work and add to the social fabric of these communities. Spending billions on trains from somewhere else tells them they’re only wanted there for their labour, and the preferences of those who got there first matter more.

Denser cities are more efficient cities. The NSW Productivity Commission found it costs up to $750,000 less in infrastructure per home in established suburbs than on the urban fringe. Denser cities are also better for the climate – a sprawling, car-dependent city pumps more CO2 into the atmosphere. And denser cities are better for the economy – allowing more employers to locate closer together increases knowledge spillovers and gives workers more options.

More fundamentally, fast trains simply would not solve the problem in the way Kohler contends they will. To be fast, trains need few stops, and few stops along low-density corridors means longer trips to the train station for commuters. Cutting fifteen minutes off a train ride from Geelong to Melbourne isn’t much help if it’s a forty-minute drive to the station, and a race against the clock to find a park before the train leaves. And at the other end, Kohler appears to believe most if not all workers need to get to the CBD. But Grattan research has found that only about 15 per cent of jobs are there, at least in Melbourne. So even after a trek to the station at one end, fast trains to the city still leave workers with more commuting to do at the other end.

The fast-trains solution would leave workers heavily exposed to one service that takes them a hundred kilometres from home. The denser-cities solution offers workers diversity and options. Some people will walk to work, some can ride their bike, others take the tram or train, and inevitably many will drive. But the key point is that when jobs are closer, it is easier for families to organise their lives – easier for one parent to pick up a sick toddler from daycare, or for the other to take a new job opportunity without upending family arrangements.

Australia’s housing affordability crisis is needlessly compounded by muddled housing policy discourse. The heart of the problem is much simpler than many let on: housing costs are too high because there are not enough houses. Kohler provides an incisive critique of the political obstacles towards remedy. The political tide is starting to turn, but there is much more still to do. Distracting Australians with the superficial solution of building trains instead of houses is an unfortunate wrong turn.

Brendan Coates & Joey Moloney

THE GREAT DIVIDE

Correspondence

In The Great Divide, Alan Kohler excavates two of the historical roots of the current housing crisis in the nineteenth century. The first was the abundance of land with low-density suburbs of free-standing dwellings sprawling further and further from the services of the CBD and little medium-density housing. This was turbo-charged in the 1950s, as car ownership grew and the suburbs spread out into farmland and market gardens – and they are still growing. The second is that land and property speculation was early established as an easy way to build wealth. This came crashing down in the 1890s when the land boom went bust, but Kohler argues that the treatment of housing as an investment asset was already well established.